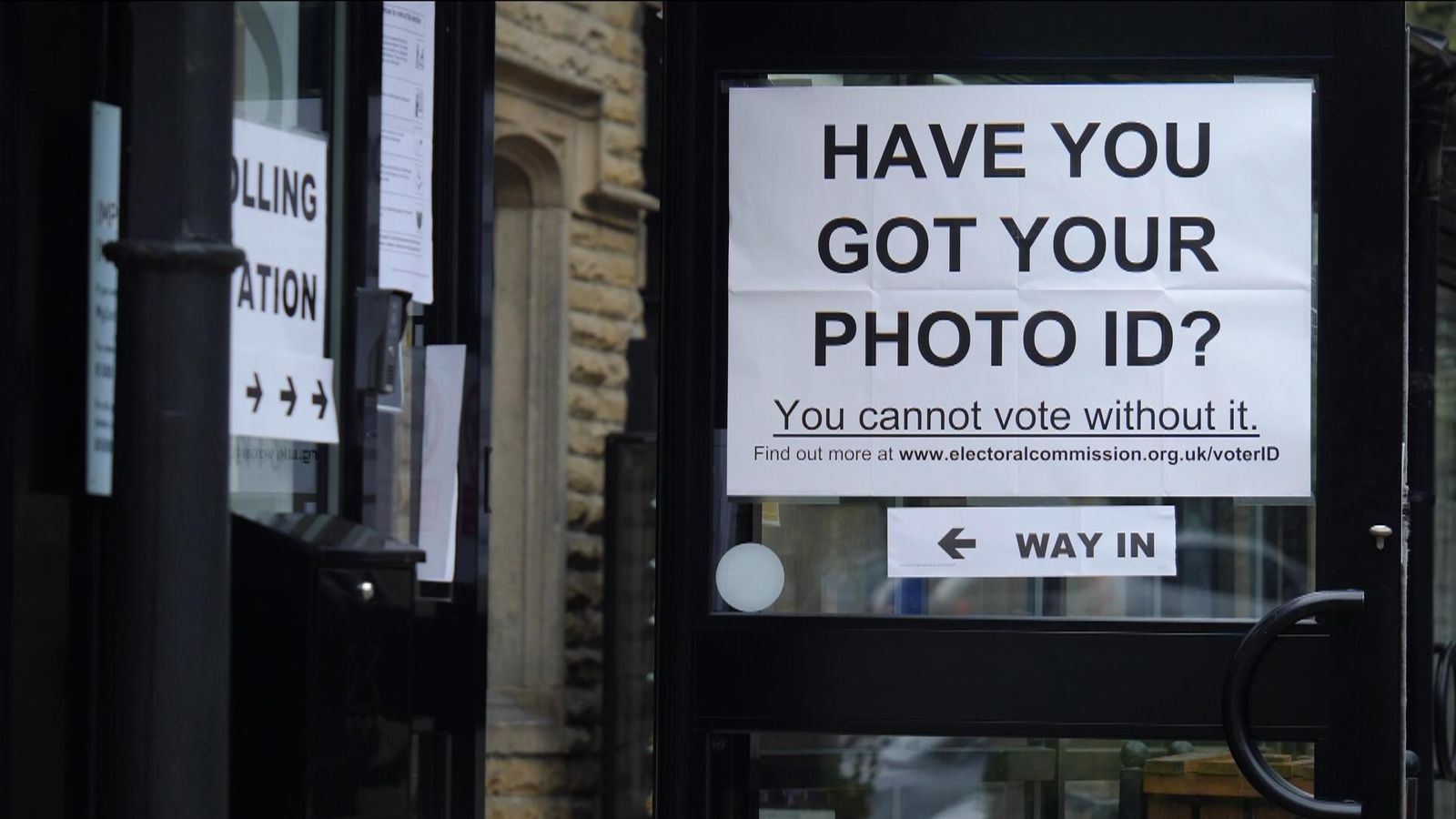

Local elections: Voters turned away at polling stations for not having the right ID

Standing outside a windy polling station in the Nottingham neighbourhood of Hyson Green, Niam sets out in passionate terms why everyone should be willing – and able – to vote.

The single mother left Sudan during the civil war in the 90s and is now anxiously trying to keep in touch with family in Khartoum.

“Every woman should vote because in our country women do not have a voice. But in this country, we should work together to help,” she said.

She says it was her daughter who told her that she’d need to bring ID.

“I am lucky, my daughter is at university, she called me and said mum you should take your ID… the council should tell the people how to vote, it’s very important”, said Niam.

Hyson Green has the largest ethnic minority population in Nottingham and there have been worries that neighbourhoods like these may be disproportionately impacted by the new voter ID rules.

Over three hours at two polling stations in the area, we spoke to 10 people who were turned away for not having the correct ID.

Thirty-six people came to vote at the Vine Community Centre between 7am and 10.30am – and of these, three were rejected.

In 40 minutes at another nearby polling station, 16 people came to vote – with two people turned away.

Advertisement

Lal and Man had photographs of their passports but were told they needed hard copies.

But 10 minutes after being turned away, they were back – proudly brandishing their IDs and keen to vote.

Others arrived with driving licences, blue parking badges and pensioner bus passes.

One taxi driver was left disappointed though after his council-issued licence was rejected.

In reality, a morning spent chatting to voters only takes us so far.

The fact that turnout in local ballots is lower than in a general election may well cloud the true impact.

Nevertheless, critics of the reforms are certain they will primarily affect areas with a younger, more deprived and more diverse population.

Nadia Whittome, the MP for Nottingham East – and the youngest member of the Commons – says the government is pursuing the policy to suppress groups who would usually vote Labour.

Ministers fiercely deny this, pointing to trial studies that show next to no impact on turnout.

But with very few instances of voter fraud, it is legitimate to ask whether this is an expensive fix to a non-existent problem.

It’s thought between one and three million people hold no valid ID.

But data on who these voters are is mixed and complex, with several different groups potentially affected.

A 2021 study suggested older people may be vulnerable because passport holding drops sharply after age 65 with lower numbers of people carrying driving licences between the ages of 45 and 60 too.

Variations between ethnicities are also smaller than some suggest with social and educational differences arguably playing a bigger role.

The government and the Electoral Commission will publish their own reports on the impact of the new rules later this year.

But even on this, there’s an argument over how data on rejected voters is being collected.

One select committee has said some people will be turned away by meet-and-greet staff on the door of polling stations and as such not recorded in the official tally.

There’s also the unknown factor of those who don’t even turn up to vote because of the new requirements.

In Nottingham, few people seemed particularly riled by the rules.

Bugsy, a Labour voter originally from Ireland, welcomed the changes as a reassuring measure at a time when some are trying to undermine elections.

“There are so many folks who want to wriggle around on the result, make it more in question,” he said, before adding with an exasperated laugh, “I suppose they’ll find a way around it in the end though”.