Scientists discover ‘origin story’ of Great Sphinx of Giza

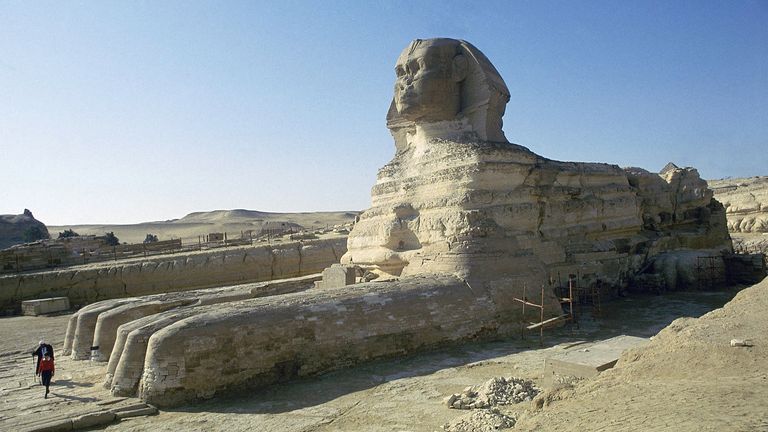

With the face of a woman and the body of a lion, the Great Sphinx of Giza has enthralled and mystified archaeologists for thousands of years.

What did it originally look like? Who was it designed to represent? These are among the popular questions historians have wrestled with.

But there is another controversial mystery – did Mother Nature play a role in its creation? Did elemental forces erode the rock formation into something resembling the mythical creature before the Egyptians came along?

That’s what a team of scientists from New York University have been trying to figure out.

“Our findings offer a possible ‘origin story’ for how Sphinx-like formations can come about from erosion,” explains Leif Ristroph, an associate professor at NYU.

“Our laboratory experiments showed that surprisingly Sphinx-like shapes can, in fact, come from materials being eroded by fast flows.”

The study centred on replicating unusual rock formations found in deserts from wind-blown dust and sand – known as yardangs.

Mr Ristroph’s team explored the possibility that the Great Sphinx was originally one of these yardangs that was then subsequently detailed by humans.

Read more from Sky News:

Elite Afghan commandos ‘betrayed’ by the British

The border crossing that is crucial in the Israel-Hamas war

Advertisement

To do this they took mounds of soft clay with harder, less erodible material embedded inside – mimicking the terrain in northeastern Egypt, where the Great Sphinx sits.

They then washed these formations with a fast-flowing stream of water to replicate wind that carved and reshaped them, eventually reaching a Sphinx-like formation.

The harder or more resistant material became the “head” of the lion and many other features such as an undercut “neck,” “paws” laid out in front on the ground, and arched “back” developed.

“Our results provide a simple origin theory for how Sphinx-like formations can come about from erosion,” observed Mr Ristroph.

“There are, in fact, yardangs in existence today that look like seated or lying animals, lending support to our conclusions.”