Libya floods: How the injustice of climate change set the stage for disaster in Derna

On the face of it there is a clear explanation for the tragedy in Derna.

Two dams across the river that runs through the city were too old and too weak to cope with an unusually heavy rainstorm.

But there’s another story written in the stinking channels of mud that carved through Derna‘s high-rises and low-lying neighbourhoods: that vulnerable places and their people will suffer the most through our failure to recognise and respond to the risks of a rapidly warming climate.

Number of dead in Libya floods soars – latest updates

That’s not to say climate change “caused” Derna to flood.

In the same way, it didn’t cause wildfires this summer.

But for both disasters, it helped set the stage – and fate decided the play.

The human errors that led to disaster

There were, of course, other very human factors that contributed to the tragedy.

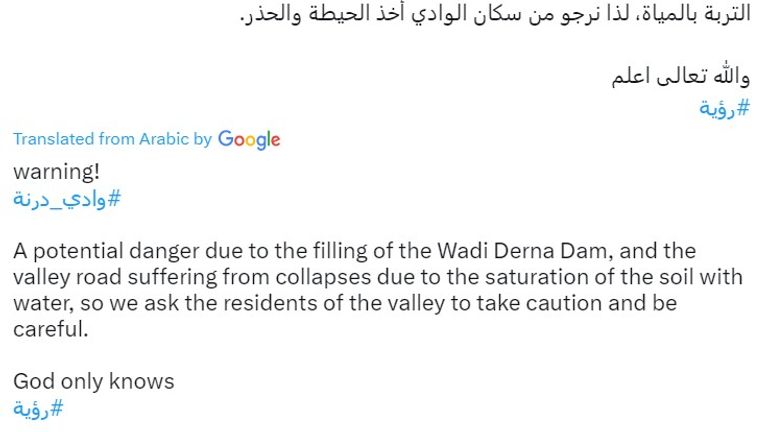

The lack of flood alerts, for example.

Then a pointless, and in retrospect possibly fatal, curfew on the night the dam burst.

Perhaps most appallingly, unheeded warnings from experts made 48 hours before that the ageing dams may fail.

The ousting of Libya’s dictator Colonel Gaddafi, back in 2011, was followed by more than a decade of political instability and civil war.

Such a volatile time for the country will undoubtedly have contributed to the lack of decent infrastructure and flood planning.

But just like there had been local warnings, internationally the connection between climate-related disasters and vulnerable countries has been known for a long time.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

2:30

Libya: ‘Residents weren’t warned’

Chances of another Derna rising for world’s poor

This spring, the IPCC – the UN panel of international climate scientists – published its sixth synthesis report on climate change.

It found that between 2010 and 2020, human mortality from floods, droughts and storms was 15 times greater in highly vulnerable regions – that’s those with fragile governments and infrastructure.

It went on to predict with “very high confidence” that those risks will increase with every increment of warming.

Derna has effectively become a case study for their next report.

Storm Daniel, which brought the deadly rains, had already dumped more than 2ft of rain on parts of Greece.

But as it travelled over the Mediterranean it was boosted by sea temperatures that were two to three degrees warmer than average for early September.

That extra warmth fuelled stronger winds and allowed the air to hold more moisture, turning Daniel into what’s nicknamed a “medicane” – a Mediterranean storm with the characteristics of a tropical cyclone.

It dumped its rain over the mountains above Derna.

In one place 414mm of rain, more than a foot, fell in 24 hours – a new record, according to Libyan weather officials.

Models predict that Mediterranean cyclones will become less frequent as the climate warms.

However, they are expected to become more intense.

Whatever is built to replace Derna’s dams may weather fewer floods like this one in future – but they’ll have to be built strong and high enough to deal with ones more extreme than what we’ve just witnessed.

A challenge for a country left chaotic and impoverished by conflict.

Read more:

The missed chances to stop the disaster

Civilians use bare hands to dig for survivors

Shortage of body bags as fears of disease rise

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

0:54

Drone footage shows flood-hit Libya

Fossil fuel profits outrage

Survivors in Derna are understandably outraged by the lack of warnings ahead of the storm and the slowness of the disaster response.

Yet there is another outrage.

Libya holds Africa’s largest crude oil reserves.

Oil and gas revenues are up; $27bn in 2022.

Yet precious little of that vast wealth has been spent on Derna – its destruction is evidence of that.

Two centuries of fossil fuel burning have driven the global warming that contributes to disasters like Derna.

Yet in the case of Libya, profits from the fossil fuel industry appear to have done nothing to help protect its people from the increasing risks of climate change.

It adds insult to the countless injuries from the flooding.

An injustice that makes Derna’s fate an abject lesson in the unfairness of the climate crisis.