‘I’m deprived of my UK citizenship but I’m not a convicted terrorist’

Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS) went from a jihadist movement once aligned to al Qaeda to forming the official government of Syria.

It was a monumental transformation for them, their country and the wider Middle East.

But potentially too for British people who went to Syria – and who were stripped of their citizenship as a result, on the grounds of national security.

Tauqir Sharif, better known as Tox, went to Syria in 2012 as an aid worker. He was accused of being part of a group affiliated with al Qaeda, which he denies, and the then-home secretary Amber Rudd deprived him of his British citizenship in 2017.

“As of now, I am deprived of my UK citizenship but I’m not a convicted terrorist – and the reason for that is because we refused, we boycotted, the SIAC [Special Immigration Appeals Commission] secret courts, which don’t allow you to see any of the evidence presented against you,” he said.

“And one of the things that I always called for was, look, put me in front of a jury, let’s have an open hearing.”

HTS is still a proscribed terrorist organisation but the British government has now established relations with it.

Foreign Secretary David Lammy travelled to Damascus to meet the jihadist-turned-Syrian interim president – the man who swapped his nom de guerre of al Jolani for Ahmed al Sharaa.

If the UK government takes HTS off the terror list, what does that mean for those who lost their citizenship after being accused of being part of it?

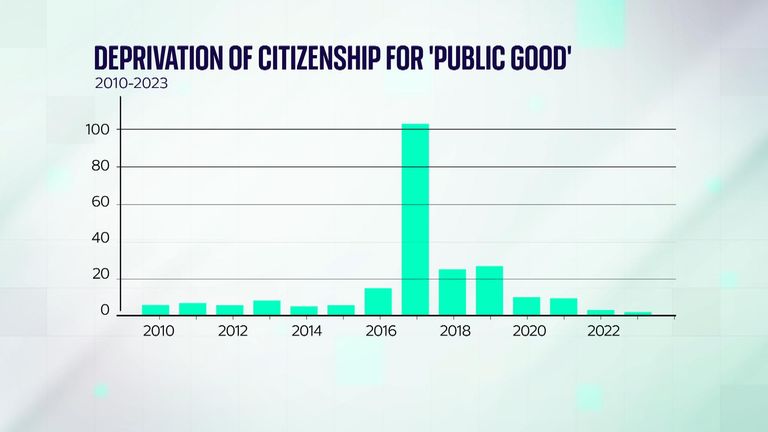

People who joined HTS are only a subset among the scores of people who have had their citizenship revoked – a tool the UK government has been quick to use.

According to a report by the Parliamentary Joint Human Rights Committee, the UK “uses deprivation of citizenship orders more than almost any country in the world”.

The peak of that was in 2017, and mainly in relation to Syria – especially in the case of people joining Islamic State, perhaps most famously Shamima Begum.

And because people cannot be made entirely stateless, and need to have a second nationality, or be potentially eligible for one, there are worries of racism in who the orders apply to.

Countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh offer dual nationality, whereas other nations do not. In 2022, the Institute of Race Relations said “the vast majority of those deprived are Muslim men with South Asian or Middle Eastern/North African heritage”.

Legal grey areas

Sky News submitted Freedom of Information requests to the Home Office asking for a breakdown of second nationalities of those deprived of citizenship, but was refused twice on national security grounds.

The independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, Jonathan Hall KC, told Sky News there are issues around transparency.

“I do think there is a problem when you have people whose relationship with the country that they’re left with is really technical and they may never have realised that they had that citizenship before and may never gone to that country,” he said.

“Me and my predecessors have all said, owing to how frequently this power is used, it should be something that the independent reviewer should have the power to review. I asked, my predecessor asked, we’ve both been told no, so I agree there’s a lack of transparency.”

Listen to The World with Richard Engel and Yalda Hakim every Wednesday

Read more from Sky News:

Menendez brothers denied parole – but they could still taste freedom

What Epstein’s right-hand woman said about Trump and Prince Andrew

UK set to bask in 30C sunshine over bank holiday weekend

No automatic reversal

Even if the government does remove HTS from the terror list, it would not automatically invalidate decisions to deprive people of their citizenship.

Macer Gifford gave up a career as a banker in London to join the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) as a foreign volunteer between 2015 and 2017.

He told Sky News that decisions “made years ago in the interest of the British public have to remain”.

Listen to The World with Richard Engel and Yalda Hakim every Wednesday

“We can’t sort of go through previous cases nitpicking through it, wasting time and money to bring it up to date,” he added.

“We can’t be naive because the intent to go out, the decision to go in itself is a huge decision for them. So it shows commitment when they’re there, they then, if they take an active participation in the organisations that they’ve been accused of joining, again, that involves training and perseverance and dedication to the cause.”

But those born and raised in Britain, who joined the same cause, and lost their citizenship as a result, might reasonably ask why that should remain the case.