‘Rishi thinks just let people die’: Dominic Cummings’ claim revealed in Sir Patrick Vallance’s COVID diary

Rishi Sunak thought the government should “just let people die” rather than see the country go into another lockdown, Dominic Cummings is said to have claimed.

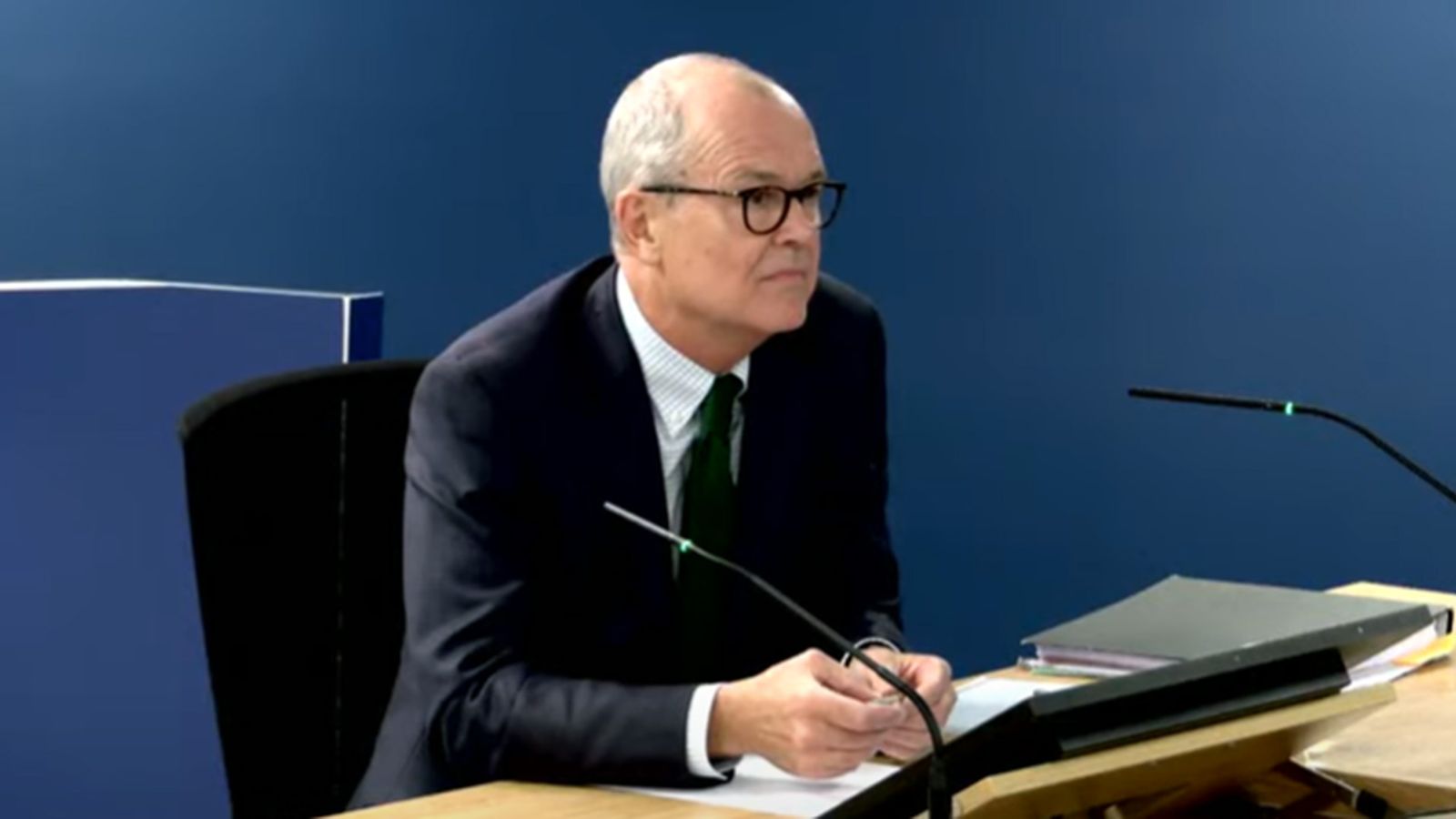

A diary entry from the government’s former chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, said Mr Cummings made the remark during a heated meeting over whether to impose stricter pandemic measures back in October 2020.

In the extract, shown to the official COVID inquiry on Monday, Sir Patrick said the then-prime minister, Boris Johnson, had argued against any lockdown, saying he was for “letting it all rip” and that those who would die from contracting the virus had “had a good innings”.

Politics live: Johnson ‘looked broken’ in COVID meetings, claims adviser

Sir Patrick then detailed a row between Mr Johnson and his chief adviser, with Mr Cummings calling for the PM to act, “arguing we need to save lives”.

The chief scientist described Mr Johnson as “getting very frustrated” and “throwing papers down” in the meeting, before saying: “Looks like we are in a really tough spot, a complete shambles. I really don’t want to do another national lockdown”.

But according to the entry, the prime minister was told “to go down this route of letting go, ‘you need to tell people – you need to tell them you are going to allow people to die”.

The meeting ended with an agreement to “beef up” the tier system being implemented across the country at the time and to “consider a national lockdown”.

Sir Patrick also wrote: “DC [Dominic Cummings] says ‘Rishi thinks just let people die and that’s OK.”

Advertisement

The scientific adviser concluded it “all feels like a complete lack of leadership” – words he stood by at Monday’s COVID inquiry hearing.

Asked about the extract by the inquiry’s legal team, Sir Patrick added: “It must have felt like a complete lack of leadership and reading it, it feels like quite a shambolic day.”

‘Risk’ of Eat Out To Help Out

Earlier in the hearing, Sir Patrick also revealed the government’s scientific and medical advisers were not told about Mr Sunak’s “Eat Out To Help Out” scheme until it was announced by the then chancellor, saying their advice about the increased risk of transmission would have been “very clear”.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

1:44

Eat Out To Help Out ‘highly likely’ caused increased deaths

Written evidence from Mr Sunak to the inquiry said: “I don’t recall any concerns about [the scheme] being expressed during ministerial discussions, including those attended by [Sir Patrick].”

Political correspondent

Sir Patrick Vallance today detailed the tug of war in government in the run-up to the first and second lockdowns – and in the course of it, made some serious allegations which Rishi Sunak will have to answer when he appears before the inquiry.

Its seriousness is not just that it comes from the chief scientist – who has no political axe to grind – but that much of this evidence is not in hindsight, but from contemporaneous notes in his diary.

The Treasury’s Eat Out to Help Out Scheme has been much picked over in this inquiry and Sir Patrick confirms the department did not seek any scientific advice before launching it and that it would have increased transmission risk.

That brings us up to the most damaging allegation against Mr Sunak

Sky News Monday to Thursday at 7pm.

Watch live on Sky channel 501, Freeview 233, Virgin 602, the Sky News website and app or YouTube.

But asked about the inconsistency with his own statement, Sir Patrick said: “Around that time lots of measures were being released and you will see repeated references in various minutes and notes and emails and indeed, I am sure, in my private notes, to our concern that people were piling on more and more things and this would come to drive R above one and I think that was discussed at cabinet as well.

“So I think it would have been very obvious to anyone that this was likely to cause, well, inevitably would cause an increase in transmission risk and I think that would have been known by ministers.”

He added: “I would be very surprised if any minister didn’t understand that these openings carried risk.”

A Number 10 spokesperson said they would not be commenting on specific evidence while the inquiry was ongoing.

But they said Mr Sunak believed it was “important that we learn the lessons of COVID, and that where lessons are to be learned, we do that in the spirit of transparency and candour”, adding: The government has submitted more than 55,000 documents in support of their work and continues to fully participate with the inquiry.”

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

2:12

Sunak explains ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme

The division did not appear to be limited to that one scheme, however, with Sir Patrick’s diaries showing how he thought scientific advisers were kept out of strategy meetings by both Number 10 and the Cabinet Office.

The adviser told the inquiry there were “periods when it was clear that the unwelcome advice we were giving was, as expected, not loved and that meant we had to work doubly hard that the science evidence and advice was being properly heard”.

He added: “There were times, because we were giving unpalatable evidence and advice, people would prefer not to hear it.”

Sir Patrick also said “pressure” was sometimes put on advisers to change advice, pointing to a WhatsApp exchange with the then health secretary Matt Hancock.

“[Mr Hancock] asked me to change something and I said no, we are not going to change our advice, because that is where the evidence bit comes in,” said the adviser. “You have got to at least see that even if you disagree with it and don’t want to do it.”

He added: “I am absolutely sure, because politicians are politicians, that there were attempts to manage us and make sure we were not always given the access we might need

“But I think overall we managed to get through all that… and make sure the advice and evidence was heard.”

Asked for his opinion on Mr Hancock after working with him throughout the pandemic, Sir Patrick said: “He had a habit of saying things which he didn’t have a basis for.

“He would say them too enthusiastically, too early without the evidence to back them up and then have to backtrack from hem days later.

“I don’t know to what extent that was over-enthusiasm versus deliberate. I think a lot of it was over-enthusiasm, but he definitely said things that surprised me because I knew that the evidence base wasn’t there.”

A spokesman for Mr Hancock said: “Mr Hancock has supported the inquiry throughout and will respond to all questions when he gives his evidence.”

Johnson ‘bamboozled’

Mr Johnson’s understanding of the science was also brought into question by Sir Patrick, who said the prime minister was left “clearly bamboozled” during a meeting between the pair about schools in May 2020.

Ten days later, Sir Patrick wrote that Mr Johnson “sways between optimism and pessimism” and he was “still confused on different types of tests (he holds it in his head for a session and then it goes).”

Another extract from June 2020 said: “Watching [the] PM get his head around stats is awful. He finds relative and absolute risk almost impossible to understand.”

And a further entry from same month said it was “a real struggle to get [Mr Johnson] to understand” graphs.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

0:33

‘Science was not Boris Johnson’s forte’

Sir Patrick again stood by his entry when questioned by the inquiry’s legal team, pointing to how Mr Johnson dropped science as a subject aged 15, adding: “He did struggle with some of the concepts and we did need to repeat them often.”

But while the senior scientist said it was “hard work sometimes to try and make sure that he had understood what a particular graph or piece of data was saying”, Mr Johnson did not have a “unique inability to grasp some of these concepts”, adding that it was “not unusual amongst leaders in Western democracies”.