Why burying power lines is an effective, but very expensive way to prevent wildfires

As deadly wildfires have destroyed communities from California to Maui, the nation’s largest utility, Pacific Gas and Electric, is making headway on its ambitious goal to move 10,000 miles of power lines in fire-prone areas underground, which would greatly reduce ignition risk.

“We’re coming off of a historic drought and those conditions are materially different than the conditions that we saw just 10 short years ago. And so now is absolutely the right time to be taking bold, decisive action with regard to the grid safety,” said Jamie Martin, PG&E’s vice president of undergrounding.

Five years ago, PG&E’s equipment sparked the deadly Camp Fire, which destroyed the town of Paradise, California, and killed 85 people. The massive liabilities drove the utility into bankruptcy, from which it emerged in 2020. But just a year later, in the same county, PG&E’s equipment started another catastrophic fire, prompting the utility to announce its extensive undergrounding plan. The utility has undergrounded 350 miles of power lines so far this year, and more than 600 miles since 2021.

While Martin says moving power lines underground reduces ignition risk by 98%, it comes at a steep cost. Data compiled by the California Public Utilities Commission shows that undergrounding just one mile costs anywhere between $1.85 million and $6.1 million, meaning PG&E’s total plan would likely be in the tens of billions. The bill would be footed by PG&E’s customers, who already face some of the highest rates in the nation.

“If we keep pushing up electricity rates, the most vulnerable of us are not going to be able to pay,” says Katy Morsony, a staff attorney with The Utility Reform Network, a consumer advocacy group that supports a more limited approach to undergrounding.

Since PG&E earns a guaranteed rate of return on capital investments, the utility is inherently incentivized to undertake more expensive infrastructure projects such as undergrounding, explained Morsony and Daniel Kirschen, a professor of power and energy systems at the University of Washington. This is how the utility makes money, not by selling electricity or gas.

“Undergrounding […] costs a lot of money. It’s a large investment. So that would increase the revenue that the utilities collect,” Kirschen explains. “Now, the question is would these other solutions be as effective as those big investment projects? That’s where the regulators have to step in.”

PG&E said in a statement that, “In the case of undergrounding, our investors’ priorities are aligned with those of our customers and our safety regulators.”

Although it’s expensive, burying power lines isn’t new. It’s common practice in city centers, where overhead lines would be obstructive, and more common in Europe overall, where cities are denser. Only about 18% of distribution lines in the U.S. are underground, though for both safety and aesthetic reasons, today almost all new lines that are built are buried.

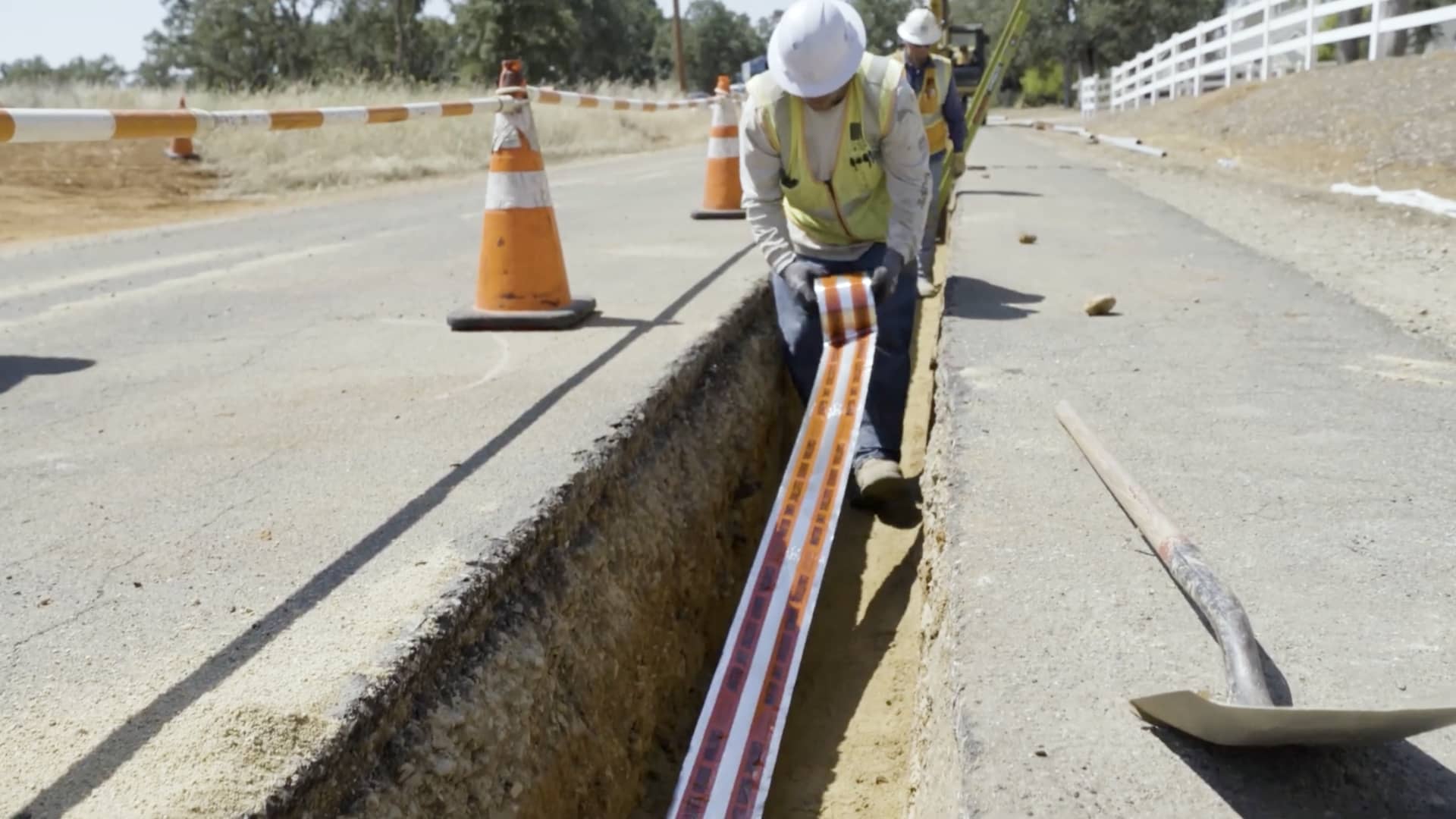

Construction workers in Arnold, California work to bury PG&E’s power lines.

Syndey Boyo

PG&E currently has about 27,000 miles of power lines underground, but these are generally not in areas of high wildfire risk. So during storms, when high winds could cause a line to topple over or a tree to fall onto a line, utilities have few good options.

“So one option is to essentially just shut down the power line, because if there is no voltage and no current on the line, there is no chance of this release of energy happening and then there is no chance of an ignition,” explains Line Roald, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison whose work includes modeling the risk of wildfire ignition and power outages in the electric grid.

Indeed, PG&E has been implementing Public Safety Power Shutoffs in California since 2019, affecting millions of people. Hawaiian Electric, the utility that could be found liable for the Maui wildfires that killed at least 98 people, has been criticized for not shutting off power in advance of high wind warnings. If the company is determined to be at fault, it doesn’t have nearly enough money to pay off residents’ damage claims.

Looked at this way, undergrounding is undoubtedly cheaper than dealing with the massive costs of deadly wildfires, and less disruptive than shutting off power completely.

“So for this one-time capital investment, we’re essentially eliminating the risk of ignition from an overhead power line by placing it underground,” Martin says.

PG&E isn’t the only utility that’s interested. San Diego Gas & Electric has a plan to underground about 1,450 miles of power lines through 2031, while Florida Power and Light is undergrounding select lines for hurricane protection. Austin Energy is also exploring undergrounding in the wake of a winter ice storm that caused weeks-long outages, and the federal government has pledged to provide $95 million to Maui to harden its electric grid, work that could include undergrounding lines.

Construction workers in Arnold, California use a piece of equipment called a rock wheel to dig a trench, so that PG&E can move its power lines underground.

Katie Brigham

But the CPUC has since released two cheaper, alternate proposals for consideration, which greatly cut back on undergrounding. One calls for moving just 200 miles underground and insulating 1,800 miles with covered conductors through 2026, while the other involves undergrounding 973 miles and insulating 1,027 miles.

Both proposals would save money but would ultimately put PG&E’s 10,000 mile goal in jeopardy. Plus, PG&E says that insulating lines is only about 65% effective at reducing wildfire risk, far less effective than undergrounding.

“If a tree falls on a line, the line is going to break and you’re still going to have a risk of a spark and you still have a chance of starting a wildfire, even if the line is insulated,” explains Kirschen.

The Utility Reform Network supports the plan to underground 200 miles, and estimates the cost of insulation to be about $800,000 per mile, as compared with the $3.3 million per mile that PG&E spent on undergrounding in 2022.

“By relying more heavily on insulated lines, we can do the work faster and we can deliver that wildfire safety more quickly to those different communities,” Morsony says.

Come November, the CPUC will decide on a path forward for PG&E, with both wildfire risk and customers’ utility bills hanging in the balance.

Watch the video to learn more about what it takes to move power lines underground.