‘Beating everything is my goal’: Inside Liam Hendriks’ journey back to MLB

Jeff Passan, ESPNMay 29, 2023, 10:00 AM ET

IN MID-DECEMBER, when Liam Hendriks squinted at the PET scan of his body and saw hundreds of spots illuminated by radioactive dye, his first thought was that he looked like his dalmatian, Olive. Hendriks was diagnosed earlier that month with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a blood cancer, and he had figured it was Stage 1, maybe Stage 2, easily treatable. The imaging — from his neck to his ankles, his blood to his bones — told a different story.

For the previous six months, Hendriks had wondered why the lymph node on the back of his neck had swelled to the size of a walnut and why the ones under his jawline jutted out and fattened his face. His wife, Kristi, saw them during a game midseason, and though she knew that the veins in his neck bulge in some photos, this looked off. Maybe it was the light hitting him in unflattering fashion or sweat warping the image. When Hendriks returned home that night and Kristi inspected the lumps, she asked what they were. Hendriks didn’t know.

A blood test came back clean, and because Hendriks was diagnosed at 18 with autoimmune hepatitis — a disease that affects the liver and flared again in 2015 — the working theory was that his body was fighting off an illness and the inflamed lymph nodes were likely a product of that. Hendriks’ back hurt more than usual, his elbow was barking, he wasn’t recovering like he once did, but hey, that’s life in the 30s for a professional athlete. He saved 37 more games for the Chicago White Sox, booked another All-Star appearance, continued one of the great stories in baseball of the past half-decade, in which a long underestimated, tossed-aside-five-times, profane, preening, impossibly nice guy emerged as one of the most productive relief pitchers in baseball.

He waited until the winter for further examination. An otolaryngologist in the Phoenix area, where the Hendrikses live in the offseason, used a needle to extract a biopsy from a node in Hendriks’ neck. The results were inconclusive, so he underwent a CT scan and kept working out at the White Sox’s facility in Glendale, going about his business as normal, until the phone call Dec. 7 that changed his life.

It was lymphoma. More tests were needed to determine the severity. The PET scan confirmed: It was Stage 4. Doctors told Hendriks that immunotherapy alone wouldn’t rid his body of the poison attacking his white blood cells. He would need chemotherapy, too. And that, more than anything before, would test the ceaseless optimism that had taken him from Perth, Australia, to the big leagues to the apex of the sport.

When Hendriks, now 34, announced his diagnosis Jan. 8, well wishes poured in from the hundreds of fans who cheered his copious strikeouts and friends who valued his more contemplative side. Gift baskets started arriving, with Preggie Pops to stem chemo-induced nausea and weighted blankets with which he could wrap himself for comfort. One wicker basket, sent by Heather Grandal, a nurse and the wife of Hendriks’ catcher with the White Sox, Yasmani Grandal, was packed with some teas for Kristi, a blanket, socks and a skull cap in case Hendriks’ hair fell out.

It also included a duffel bag in which he could carry items to his infusion sessions. At first, Hendriks didn’t notice the words on one side of the bag. Kristi alerted Hendriks to them, and when he flipped the bag right side up, it spelled out what over the previous month he’d come to believe.

“CANCER MESSED WITH THE WRONG MOTHERF—ER.”

ANDREW VAUGHN STILL laughs at what he saw that mid-January afternoon. The White Sox’s first baseman and his wife, Lexi, swung by Hendriks’ house in Scottsdale to visit. Vaughn’s sister-in-law had non-Hodgkin lymphoma in recent years, and he knew the necessity of support. Vaughn was struck by Hendriks’ unrelenting positivity, which was clearest when he pulled out his phone, opened a calendar app, flipped to May and gestured at it.

“That’s what I’m shooting for,” Hendriks said.

Two days after his first treatment for Stage 4 cancer, Hendriks had already pinpointed when he wanted to be back on a big league mound. It was audacious, hubristic even, but Vaughn knew better than to doubt his friend who had willed himself from nothing to a star, who stared down the baddest men in the sport, challenged them to a my-best-versus-yours contest and almost every time emerged victoriously.

“I want to be the best version of myself as I can be,” Hendriks says. “Everything I do is trying to beat something. Whether it’s beat the opponents into oblivion or … “

“Beat cancer,” Kristi says.

” … beating the date that I think I wanted to be back at,” Hendriks continues. “That is my goal at all times. Beating everything is my goal at all times.”

This has been Hendriks’ reality for as long as he can remember. His father, Geoff, played Australian Rules Football professionally, and with plenty of bulk on his 6-foot frame, Hendriks could’ve done the same. (At 15, he had played on a national football team with Patty Mills, now a 14-year NBA veteran.) But football was the backup plan. Baseball was the dream. More than any game he had tried, it brought out in him something raw and pure. Baseball, Hendriks says, is about “the competitive nature and the drive to succeed and the will to kind of embarrass the other guys’ families. Until you get to that point, you’re almost OK with mediocrity. I need to go out there, and if I’m not completely eradicating them from the face of the earth … I don’t have a middle ground. I want to eviscerate you, or you’re OK. And I much prefer the evisceration.”

Summoning that took years to wrangle. In 2007, just six years after he nearly quit baseball when he was in the first round of cuts at tryouts for his state-level team, he signed with the Minnesota Twins at 18 for $170,000. In 2010, then a starting pitcher, he nearly won the minor league ERA title. He ascended to Triple-A the year after, more command-and-control artist than embarrass-eradicate-eviscerate vanquisher, with a low-90s fastball and five times as many walks as strikeouts. The Twins summoned him to the big leagues in September 2011, and it wasn’t until more than a year later, in his 18th career start, that Hendriks notched his first win. He was enough of a nonentity that Boston manager Bobby Valentine once wrote out a lineup card filled with right-handed hitters because he thought the “L” in “L Hendriks” meant he was left-handed.

By the end of the 2013 season, the Twins saw Hendriks, 24, as a AAAA player — too good for Triple-A, not good enough to succeed in the major leagues, with a 2-13 record and 6.06 ERA in 156 innings over 30 games. Minnesota cut him in December and he was quickly snatched up by the Chicago Cubs, who 10 days later let him go to the Baltimore Orioles, who held onto him for two months and took him off their roster as spring training began in 2014. Toronto pounced, snuck him through waivers, sent him to Triple-A, called him up for three starts and traded him to Kansas City in July. The Royals toyed with making him a reliever but didn’t see much growth potential there either, and in October, Hendriks was designated for assignment for the fourth time in less than a year, the standard path for a dead-end career.

Hendriks resuscitated it in 2015, rejoining Toronto, transitioning full-time to a relief role, adding nearly 4 mph to his fastball because he could go max effort in shorter stints and posting a 2.92 ERA in 64.2 innings. The Blue Jays traded him that winter to Oakland, where Hendriks settled in as a middling middle reliever, fungible enough to be DFA’d again in 2018 with no bites from the other 29 teams. Their baseball life on the precipice, Hendriks and Kristi, who married in 2013, grasped for help and found it in a most unusual place.

Kristi had seen an Instagram post from the actress Sarah Hyland in which she talked about Rubi Sandoval, a Tarot card reader and healer in Southern California. Kristi reached out to Sandoval and encouraged Hendriks to talk with her. Sandoval noticed something immediately: Hendriks’ self-involvement caused him to ask, “Why?” with things he couldn’t control. She knew nothing about baseball — she called the pitcher’s mound “the mount” — but Sandoval did know that wondering why the manager was giving others opportunities Hendriks believed he deserved led nowhere good. She encouraged him to stop shouldering the burden of his own expectations, much less others’, and instead appreciate what he has. If this was indeed the end of his career, at the very least he shouldn’t sabotage himself with shackles of his own making.

“I knew I needed to have what they call white-line fever, where I’m a different person on the field than I am off the field,” Hendriks says. “If I’m going to go out, I’m going to go out on my own terms.”

So he stopped running. He gave up traditional workouts. He started long-tossing as far as he could. He watched baseball’s attitude relax toward on-field displays of emotions and screamed after big strikeouts and f-bombed his way through bad pitches. He was angry that everything had come to this, and, he learned, he pitched better angry.

“He just went out there and just started throwing because his job and his life depended on it,” Kristi says. “And I think Liam always does the best when he is backed into a corner. … You can get so wrapped up in what is expected from you from teams, expected from you from fans and things and [Sandoval] just brings a calm, cool [presence] that resets his feelings, his emotions and his purpose out there on the mound. Everybody has their own thing. I know people think that we’re crazy when we say that we do these things, but we don’t care. It works for us.”

In 2019, Hendriks made the A’s Opening Day roster and worked his way from the middle innings to higher-leverage spots to the closer role. He put up more wins above replacement than any reliever in baseball. He learned to balance the fierceness of his on-field persona, spending his time off the mound playing with the couple’s 10 adopted pets or building Lego sets or getting lost in young adult fiction books. Finally, everything was clicking. The next season, he led MLB relievers in WAR again, and the White Sox, in search of a closer, lavished him with a three-year, $54 million contract in free agency during the winter of 2020. Hendriks followed with a third consecutive year topping the WAR reliever leaderboard in 2021.

He thinks about that 2021 season sometimes, not because his 113-7 strikeout-walk ratio was the second best in baseball history, behind only Dennis Eckersley’s 1990 season, or because he successfully fulfilled his end of the big money contract. It’s because when Hendriks saw the PET scan for the first time and studied it, he noticed the spots in his hips were bigger than the ones in his neck. That meant they’d been growing even longer. And it occurred to him that not only was it likely that he had pitched the entire 2022 season with cancer, there was a good chance he’d been throwing in 2021 with it, too.

WHEN SHE WAS 24 years old and in medical school for orthopedics, Allison Rosenthal was diagnosed with leukemia. For the next 2½ years, as she underwent chemotherapy, it dawned on Rosenthal that as much as her chosen field had fascinated her — she was an elite gymnast and competed collegiately for Utah State, and she wanted to help athletes — something else was calling her.

“Because of my life experience, it steered me in a different direction,” says Rosenthal, today an oncologist and hematologist at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix. “And here I am now helping other people, paying it forward best I can because somebody saved my life so that I could do it for others.”

Rosenthal met Hendriks and Kristi in late December, about two weeks after the Dec. 7 call from Dr. Paul Charnetsky, in which the only words Hendriks remembers are: “There’s a possibility it’s lymphoma.” Kristi was at the dining room table, working on a five-minute gratitude journal, when Hendriks called to tell her. And as stoic as he was trying to be, as strong as he felt like he needed to be, it couldn’t erase the panic that coursed through her. Five days later, when another biopsy confirmed that the nodes were hard, a telltale sign of lymphoma, Kristi took a still slightly sedated Hendriks home, helped him to bed, went into their walk-in closet and cried for 10 minutes. And then there was the first call with Rosenthal, a lymphoma specialist, in which she tried to explain what the Hendrikses already knew from all the panic Googling they were doing: Lymphoma is the most common blood cancer, diagnosed in around 90,000 people a year in the United States, and while it’s curable with a long life expectancy, it’s easier if caught earlier, and they’d need to do more testing to determine the severity.

So Hendriks went in for the PET scan, the one that made him look like Olive the dalmatian, and Rosenthal at first shattered the Hendrikses’ illusions when she said Stage 4. It was not, she made sure to say, necessarily terminal like other Stage 4 cancers; Stage 4 non-Hodgkin lymphoma simply means the cancer cells have spread beyond the lymph nodes and to other areas — in Hendriks’ case, his bones. This was serious, yes, but as the tears again welled in Kristi’s eyes and Hendriks tried to maintain his steely resolve, Rosenthal uttered 10 words that brought them a semblance of calm in a sea of concern.

“I’ve been worried before,” she said, “but I’m not worried with you.”

There was a path to remission. It would involve grueling eight hours-long intravenous immunotherapy sessions that target B cells — a white blood cell that makes antibodies to keep the immune system afloat — infected by cancer. The normal immunotherapy-chemotherapy treatment for Stage 4 non-Hodgkin lymphoma is six courses, each two days in a row followed by a 28-day break. Hendriks nodded along at everything but the six treatments. Might four be enough to cure him? He wanted to return to the White Sox as soon as possible, and six months of infusions would keep him out until at least August. Rosenthal was open to the possibility.

“I certainly understand the commitment that competing in athletics at an elite level takes, and I understand what a big part of your life that is when you’re an athlete,” she says. “That’s your primary identity and main way that you make a living. So I think I could identify easily with Liam and how important sports were to him and how all of the determination and skills and competitiveness and everything was going to factor into how he was going to respond to the cancer diagnosis and what he had to do to get back to playing.”

With the treatment set, Hendriks and Kristi told almost no one, including immediate family members. They didn’t want to ruin Christmas. Even close friends didn’t find out until Jan. 8, when the Hendrikses sent a text about Liam’s diagnosis and prognosis, adding that they’d be announcing the news on social media a half-hour later. Spring training was soon approaching, and even if they could keep it secret for another five weeks, eventually the reason for Hendriks’ absence would raise questions.

Treatment started the next day. Hendriks arrived at 6 a.m., his inscribed duffel bag in tow, loaded with an iPad, a book, headphones, chargers, enough to keep him busy for the next 10 hours as the medicine went to work. Nurses inserted an IV into his left arm — always his left arm, Hendriks requested — and within a half-hour, he was conked out. He slept like a log that night, returned for a second day of infusions and spent the following two days, he says, “pretty much catatonic on the couch.” Immunotherapy and chemotherapy took a toll. The stomach pain. The jaundiced skin. The drugs were killing healthy cells, too. And they wouldn’t know for at least a month whether they were working at all, let alone ridding him of the disease.

Sometimes Kristi would wake up in the middle of the night crying, catastrophizing about losing Hendriks, about all the incredible things they were supposed to do that cancer might steal from them. Then she would listen to Hendriks, eternally sunny, back at the White Sox’s complex playing catch three days removed from his first chemo session. He never forgot what Sandoval, the Tarot card reader, had told him about asking why. The instinct to say “Why me?” can haunt cancer patients, so Hendriks flipped the question on its head.

“Out of all the people I know, why not me?” he says. “I feel like I am capable of handling this challenge a lot better than some, a lot worse than others, but a lot better than some. If I can do that while having the support of an amazing family, an incredible wife and a bunch of little furry babies running around, then why not me? I know that I can handle this head-on and attack it, and no matter what happens, a lot of good is going to come from this. …

“I like shouldering the burdens for whatever reason. I don’t know. I always take it back to when I was in high school. We went on a camping thing with school. And I was the guy who was walking up with a bag, going down and getting two more bags, and walking up because some other people are struggling. For some reason that always clicks into my head, but I like being there.”

In between sessions, to kill the time he’d normally be spending preparing for the season, Hendriks sequestered himself in the garage, built Legos and listened to podcasts. The White Sox — whose “exceptional” treatment of him, Hendriks says, included allowing him to park at the stadium in owner Jerry Reinsdorf’s space — brought him a lime-green Lamborghini set to build. He constructed the Titanic out of more than 9,000 bricks. Then an AT-AT walker and Starship Destroyer and BD-1 from the Star Wars universe and a McLaren F1 supercar and a Fender guitar and even a bonsai tree.

He heard from well-wishers — out of nowhere one day, Luis Arraez, the Miami Marlins‘ hitting impresario and Hendriks’ lockermate at the All-Star Game last year, FaceTimed him with reigning National League Cy Young winner Sandy Alcantara to send their best — and let them distract him from the nausea and hot sweats. In March, he got lost in the wonder of the World Baseball Classic rather than another bone marrow-harvesting session, in which doctors drilled into the back of his hip to take a sample that would help track his progress.

Rosenthal alerted Hendriks and Kristi to the progress after the third session, typically the halfway point of treatment. It was working. The spots on the PET scan were almost all gone. The lumps had receded. The marrow test looked good. They could cut the infusion rounds to four, and his last would start April 3, the day of the White Sox’s home opener. He fell in and out of sleep that afternoon, hoping the end was near.

Seventeen days later, Hendriks returned to the Mayo Clinic for a PET scan. He hadn’t had coffee yet that morning, so he and Kristi went to a Starbucks nearby. His phone beeped with a text message. It was Rosenthal. The results were in.

“Hey boss,” the message read. “PET looks great, so let out a big breath, try not to yell, ‘f— yeah’ too loud if you’re still on campus and give your amazing wife a big hug. See you guys soon.”

They scurried back to the hospital. Hendriks’ stone face belied the joy that suffused his body. Kristi teared up. Rosenthal looked at her and said, “There’s no crying in baseball.” When Hendriks rang the bell to signal that he was cancer-free, Kristi locked eyes with Rosenthal again, and both of them started to bawl.

Now, like Rosenthal, the Hendrikses are looking for ways to pay it forward. Research and support for adolescent and young adult cancer — defined as patients ages 15 to 39 — is wildly underfunded, and the Hendrikses want to change that. Their first time at Mayo Clinic, they had seen a shop with dozens of mannequin heads topped with wigs. While Hendriks did not lose his hair, plenty of people do — and many among them can’t afford a wig that can offer dignity and comfort and the sort of positive feelings Hendriks and Kristi believe helped him through the process. Insurance often doesn’t cover the cost, either. The Hendrikses asked the hospital how many total wigs they had in stock and what they would cost. When told, they cut a check for $24,000 and asked Mayo Clinic to distribute them to anyone for whom the cost would be prohibitive.

“It was an unexpected and a really generous gesture on their part that just proves the fact that despite going through everything that he did the whole time, they were wondering how they could help other people,” Rosenthal says. “And if that doesn’t speak to the character of the Hendrikses as a team, I don’t know what does.”

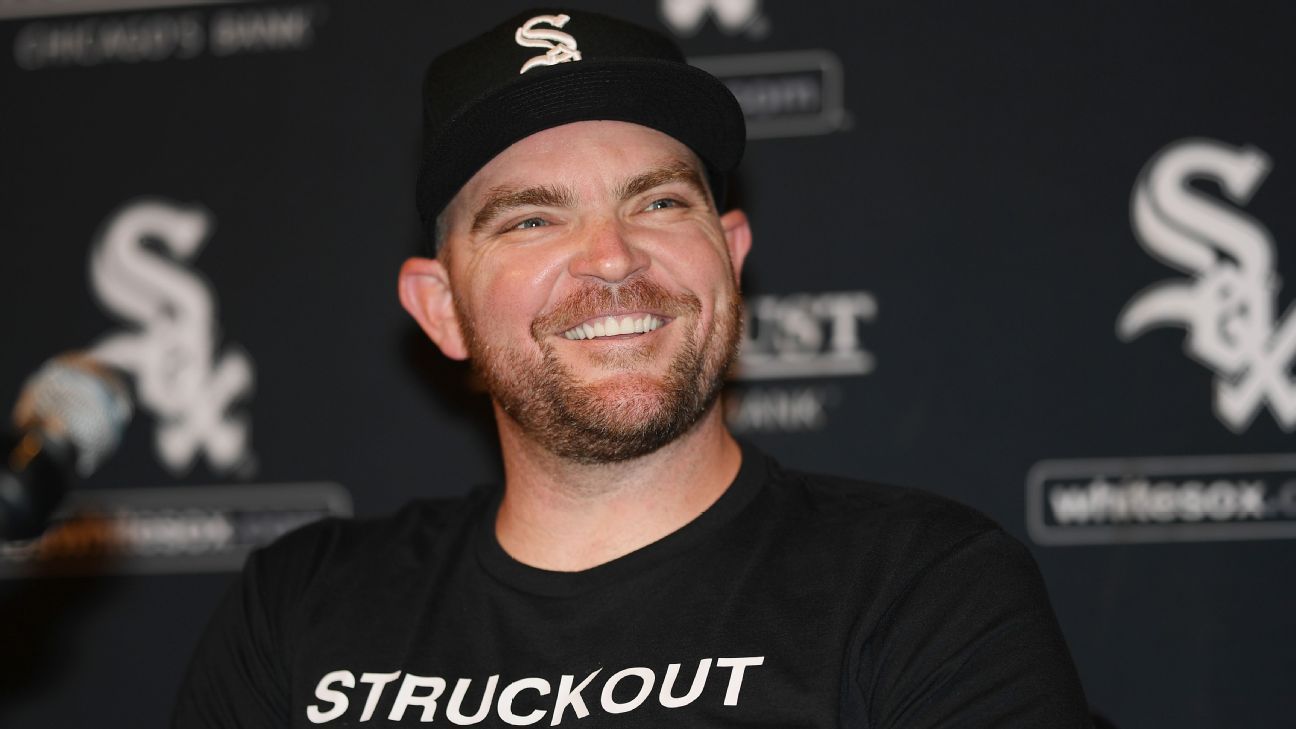

EARLIER THIS MONTH, on the final leg of his return, Hendriks arrived in Charlotte for a rehabilitation assignment with the White Sox’ Triple-A affiliate wearing a shirt that said, in all caps, “STRUCKOUT CANCER.” He was his typically magnanimous self — Hendriks summoned a different food truck to the ballpark nearly every day and offered to buy lunch for his teammates and opponents — and made time for those who sought advice or selfies. But he was focused: He knew this was real, with near-big-league caliber hitters to get out if he wanted to fulfill his prediction to Vaughn.

As easy as Hendriks made baseball seem the last four seasons, pitching after cancer, he’s learning, isn’t exactly a get-on-the-bike-and-ride-it exercise. His stride length felt wrong for weeks. He wasn’t ripping through sliders with his typical ferocity. His fastball had lost a couple ticks, and while they’ll probably come back, only a true believer would rely upon anything because of the past. But then belief helped Hendriks return, so who’s to question it?

“I still remember her saying,” Hendriks says, looking at Kristi, “‘at some point, something has to not be worst case.'”

“Because it’s the rule of thumb in baseball,” she says. “Eventually that ball’s not going to drop in anymore.”

“Eventually,” Hendriks says, “you’re going to get an out.”

Today is that day. The White Sox plan to activate Hendriks this afternoon. He wanted to return at home, to give fans at Guaranteed Rate Field who have seen far too much bad baseball from the White Sox something to cheer for. He coveted a return in May, being back on a major league mound less than six months after the pain of the first treatment — and that the White Sox are facing the Los Angeles Angels, and Hendriks could be standing 60 feet, 6 inches from Shohei Ohtani and Mike Trout, makes it that much better.

He has been yearning to go through his full routine: Spend the first four innings in the clubhouse, head to the bullpen, don’t move until the phone rings and the word “Liam” echoes, throw a few warm-ups, whip off the arm sleeve to signal it’s time, tighten the belt, slug 4 ounces of pre-workout loaded with 300 milligrams of caffeine, run in to a Queen/Rage Against the Machine/Prodigy/Skrillex mash-up and embarrass, eradicate, eviscerate. When he gets his first strike, his first expletive, his first out, his first inning, his first save, he’ll hear so many of those noises he missed and reckon with the cognitive dissonance of knowing he was too close to never hearing them again.

“One of the most difficult parts of being a cancer patient is actually survivorship, believe it or not, because when there’s a problem and there’s a plan for the problem, you come and you get it done,” Rosenthal says. “You show up for your appointments, you get the treatment that’s been prescribed and then we tell people, all right, we fixed it. Looks good for now. And then we send people out with a plan for follow-up, but sometimes that’s the scarier part, because somebody isn’t checking in with you every day and somebody isn’t able to tell you, oh, that ache you have in your knee today isn’t something to worry about, you slept funny. Survivorship is its own thing that people have to navigate through.”

He’ll have help. Rosenthal will always be a phone call away if necessary — and she’s planning on heading to Chicago on Sept. 15, not to see her beloved Cubs but rather to join Hendriks on the South Side for the White Sox game on World Lymphoma Day. He’ll have the rest of his family who looked after him and the teammates who kept him in good spirits. He’ll have the fans whose messages resonated. Around this time last year, he couldn’t have imagined this future. A lump showed up and life got scary and the control that is his hallmark on the mound didn’t exist off it.

“In cancer, there are days when I’m 99% for him and he’s 1%,” Kristi said. “And there are days where I’m just so beside myself in the sense of, I just feel so much pain for him that he’s 99% for me. I feel that when you get married, you know, oh, 50/50. And I just think as marriage actually continues on, you realize it’s not like that at all. And my heart goes out to every cancer patient, every cancer survivor actually. Because the day you are diagnosed with cancer, you become a survivor. It is such an overwhelming thing. But there is still so much life to be lived. And I hope that what he does on the field encourages a lot of people to know that you can get through this and there’s just so much happiness when you just live.”

How does someone who could have died live? In Hendricks’ case, he lives like the boy who ascended the mountain, came back down again and recognized the climb back was his duty, like the man who refused to ask why and instead asked why not, like the husband who said everything was going to be all right and wasn’t lying.

He lives like the motherf—er cancer messed with and lost.