Hijacked – Flight 73: The hostage who survived the 1986 Pan Am plane attack – and has now been told why by one of the terrorists

Wearing a red duvet jacket, an old T-shirt and a Panama hat, all of which had seen better days, Mike Thexton stood out like a sore thumb when he turned into the business class section of Pan Am Flight 73.

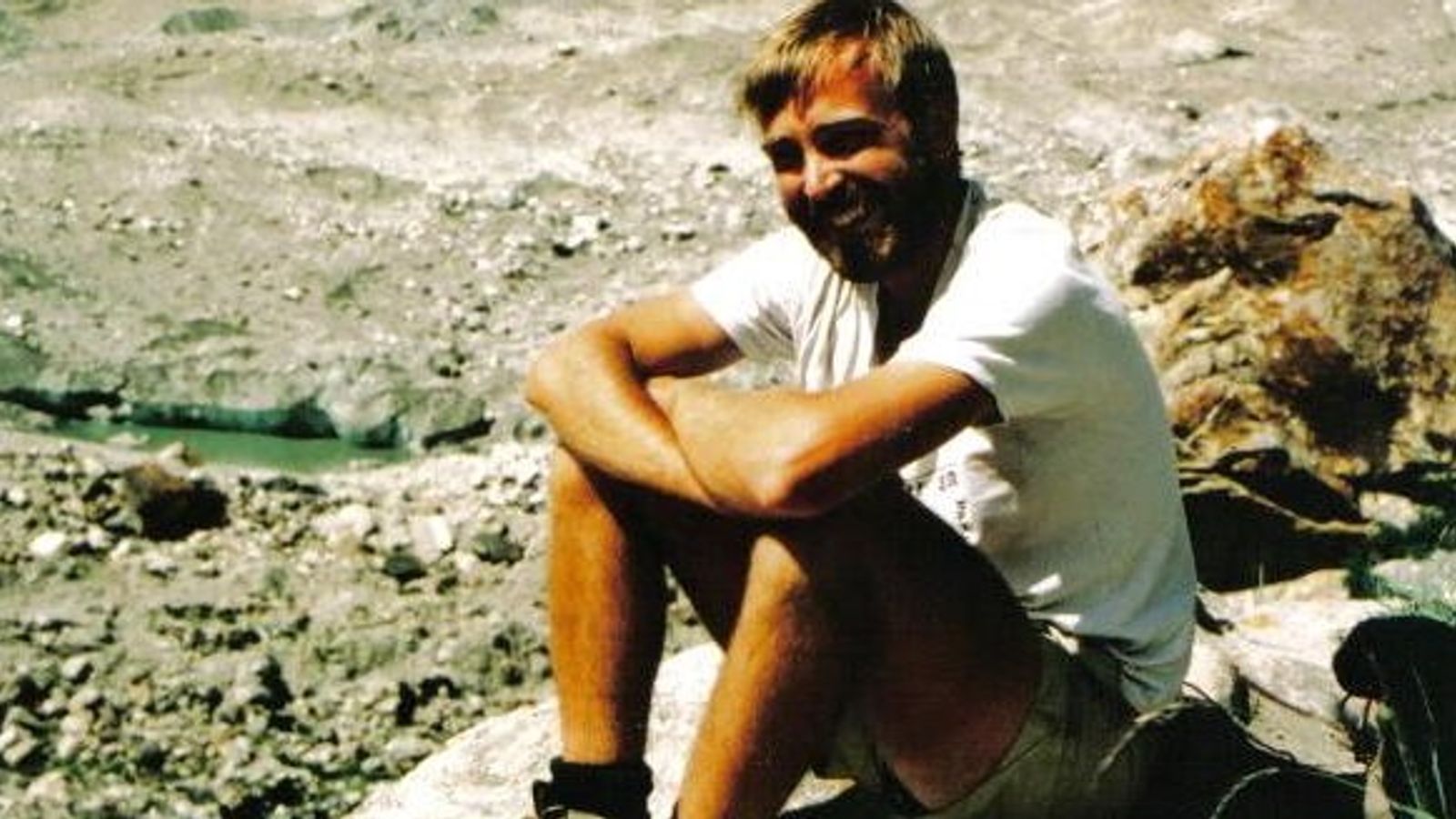

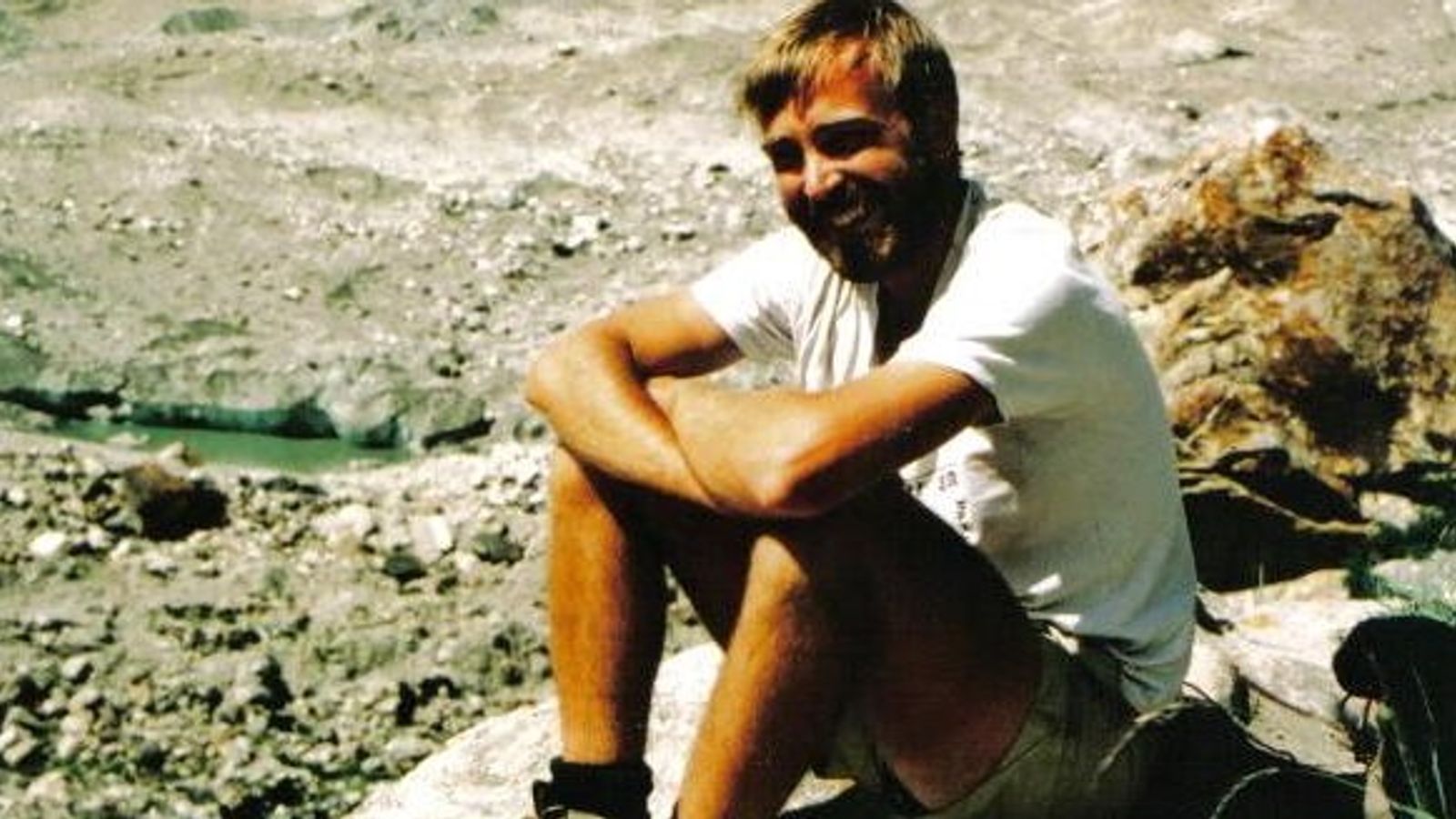

It was 5 September 1986, the plane sitting on the tarmac at Karachi airport in Pakistan in the early hours of the morning. Desperate for a decent night’s sleep and good food as he made his way back to the UK from a mountaineering trek, Mike had swapped his flight to get home a little earlier and decided to upgrade for the first time in his life.

“I can still call to mind the feeling as I put my bag down on this very big seat,” he says now. “I took out a book and thought: this is fantastic.”

The plane never took off. As it sat on the runway, Palestinian terrorists dressed as security officers stormed the aircraft, armed with Kalashnikovs, pistols and explosives; it was the start of a terrifying 16-hour ordeal for almost 400 passengers and crew on board.

Mike, aged 27 at the time, was taken hostage towards the start of the hijack after the terrorists collected passports and called his name. A gun was pointed towards him.

“By then, I was never in doubt they would shoot me,” he says. “I thought: somebody is going to die today, and it’s going to be me.”

In the end, the majority of the killing was indiscriminate; guns were fired and explosives detonated in darkness as the plane’s power went down after about 15 hours. Twenty-one people died and more than 100 were injured; but despite his initial call-up, Mike was spared.

Almost 40 years later, his story has had an extraordinary update. As part of a new Sky feature documentary, Hijacked: Flight 73, he was able to have a conversation with the man who held him at gunpoint – and discovered there was a reason he left the plane alive.

It starts with the motivation for his trip: his brother, Peter Thexton.

‘It was important to me to see where my brother died’

Peter was a doctor and a climber who had died three years earlier, aged 30, on Broad Peak, the 12th highest mountain in the world.

Following an unsuccessful attempt on Everest in 1980, Peter was part of a group aiming to climb K2 and used the nearby Broad Peak, on the border of Pakistan and China, for acclimatisation to extreme altitude. During the trek, he developed fluid on his lungs and had to be lowered down to a high camp at 24,000ft. Despite efforts to save him, he died during the night.

Mike, now 63, from southwest London, wanted to honour his big brother. “It was important to me to see where he died,” he tells Sky News. “It was only years later when I had children of my own that I suddenly thought about my parents, that they would have not wanted me to go.”

On the plane, his first realisation something was wrong was when he heard shouting. Then he saw a man struggling with a flight attendant.

“He had a pistol in his hand, his arm wrapped round her. I remember thinking: that’s a man with a gun, how extraordinary. I didn’t duck or run away or go to help or anything, I just stared like an idiot.”

‘I was told to kneel in the doorway’

It quickly became apparent the militants’ hijack was not going to plan. The large aircraft, a jumbo jet, had an upper floor and there was confusion over where the cockpit was located, giving the pilots time to escape – and therefore no chance of the plane being under terrorist control in the air.

The terrorists were part of the Abu Nidal Organisation (ANO), which was responsible for several attacks in the 1980s; the plan for Pan Am 73 was to force the pilots to fly them to Cyprus and Israel, where other members of their militant group had been jailed on terror charges. Rajesh Kumar, 29, was the first passenger to be shot dead following failed attempts to negotiate with officials on the ground for the pilot to return.

When Mike’s name was called out, he got up. “I didn’t look much like my passport photo after a couple of months in the mountains, but I knew they would find me anyway. I felt I had to do what I was told.”

He remained calm. He had not witnessed the death of his fellow passenger, but flight attendants had. He was asked if he was carrying a gun by the group’s leader, Zaid Hassan Abd Latif Safarini. “It was the most ridiculous question. I was probably very close to hysterics, I just burst out laughing… and then he told me to kneel in the doorway.”

The conversation with a killer

Crew members around him were in tears. Mike attempted to appeal to his captor. “‘Please, please don’t hurt me. My brother has died in the mountains, my parents have no one else’. He just waved his hand as if to say, I haven’t got time for that. That’s not important. In effect, I’m going to do what I’m going to do, and you don’t really matter.”

He was left in the doorway for several hours, convinced he was going to die. In an attempt to connect with the attackers, he prayed, touching his head to the floor. “I stayed very calm,” he says. “I’d spent a couple of months in the mountains, mainly thinking about my brother and his death, and I just felt terribly sad for my parents. They had lost my brother… and then this.”

The hours rolled on and Mike eventually fell asleep. “People ask how, but I was exhausted. It’s very tiring being afraid for that long.” He remembers being woken by one of the terrorists kicking his feet. “‘Up, up, move’, he said, and put me back with the others. I couldn’t understand it.”

As the power went off and the shooting began, Mike made his escape as people poured out on to one of the wings of the plane. Like many others, he jumped. “For so many years afterwards, I thought about why they didn’t shoot me when they had the chance.”

The Hijacked documentary gave him the opportunity to find out. Producers had made contact with Safarini, who is serving a 160-year sentence in the US after originally being jailed in Pakistan for 15 years.

“I thought long and hard about it,” says Mike. “I certainly didn’t want people watching this film thinking I was having a friendly conversation with the man who killed all those people. But it was an opportunity I had to take.”

He had never forgotten the man he thought would end his life. But perhaps surprisingly, Safarini also remembered Mike Thexton. When Mike asked him why he was spared, he told him it was because of his brother. “I was speechless. It never occurred to me that he had even paid any attention, or cared, 12 hours earlier when I had told him that. It was stunning.”

The hero flight attendants

Mike is one of a number of survivors who share their stories in the new documentary. Another is Sunshine Vesuwala, who had been a flight attendant for just six months before the attack.

She remembers getting on the plane that day and noticing the doors were missing from a storage cabinet. “It was kind of swinging and had no support at the bottom,” she tells Sky News. “It was a little worrisome. But it was actually the best thing because we managed to shove people into the galley under the counter, and they were saved.”

When Sunshine first saw a man dressed in a security uniform holding a gun to a passenger’s head, she wasn’t afraid. “We thought there was something wrong with the passenger, that he was a smuggler or something,” she says. Then he grabbed flight attendant Neerja Bhanot. “That was when we realised it was us they were after.”

Before the attackers could find the pilots, Sunshine was called. “I was on my knees in the aisle; everyone had to put their hands in the air and just be quiet. He called me up – ‘you, come here’ – so I got up and I went.” She was asked to point out the cockpit and tried to stall. When the attackers realised the pilots had left, they asked her if they were men. “I said yes. He said they had run away, and he laughed.”

But it was the best thing the captains could have done, she says. “Any little thing in flight, under pressure… we didn’t know what they were up to and it basically comes down to lives being saved.”

When the attackers asked for passports, Sunshine helped collect them. She hid those of white Americans, fearing they would be targeted. As the hours passed, she listened out for the attackers potentially revealing each others’ names, writing them down on plasters she was carrying for potential identification later.

“I really didn’t think we’d survive,” she says. “It was a question of delaying the inevitable.”

When the lights went out, a passenger managed to open a door amid chaos as the attackers started firing. “I could see people running. They got on to the wing and some were jumping. Everyone was in a panic. So I went out and whoever was going to jump, I let them jump. The wing was full and there was no way I could control the crowd.”

Rather than jumping herself, she went back into the plane with another crew member to help those who needed it. Her colleague Neerja had done the same. Sunshine found her inside, injured. “She collapsed on the floor. We carried her and pushed her down [a slide that had been inflated].” Neerja was still alive at this point, says Sunshine, but later died of her injuries.

When she herself was back on the ground, her first thought was to find Mike.

“He was a hostage in the front for a very long time and I was worried,” she says. “I didn’t know whether he was alive or dead. I saw him and just grabbed hold of him.”

Mike went on to write a book about his experience, What Happened To The Hippy Man? Now, he is pleased to have some answers about the ordeal – and how his brother’s story saved his life.

“I think [Safarini] thought that this person has lost somebody who was close to him,” he says. “Then it just becomes that little bit harder to shoot him. I was a real person, and I’d lost my brother.”

Hijacked airs on Sky Documentaries and Now from 29 April