Breakthrough nuclear fusion experiment could ‘revolutionise the world’ with clean energy

US scientists have carried out the first ever nuclear fusion experiment to achieve a net energy gain, paving the way for a “clean energy source that could revolutionise the world”.

During a landmark news briefing at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, officials revealed the successful fusion experiment had taken place last week.

As it happened: ‘Amazing’ scientific breakthrough could create limitless energy

It was the result of “60 years of global research, development, engineering, and experimentation”, which could eventually become the backbone of commercial electricity generation.

Such a result would supercharge the world’s shift to renewable energy, helping to fight climate change.

US energy secretary Jennifer Granholm said the breakthrough “will go down in the history books”.

“This is one of the most impressive scientific feats of the 21st century,” she added.

How was the experiment carried out?

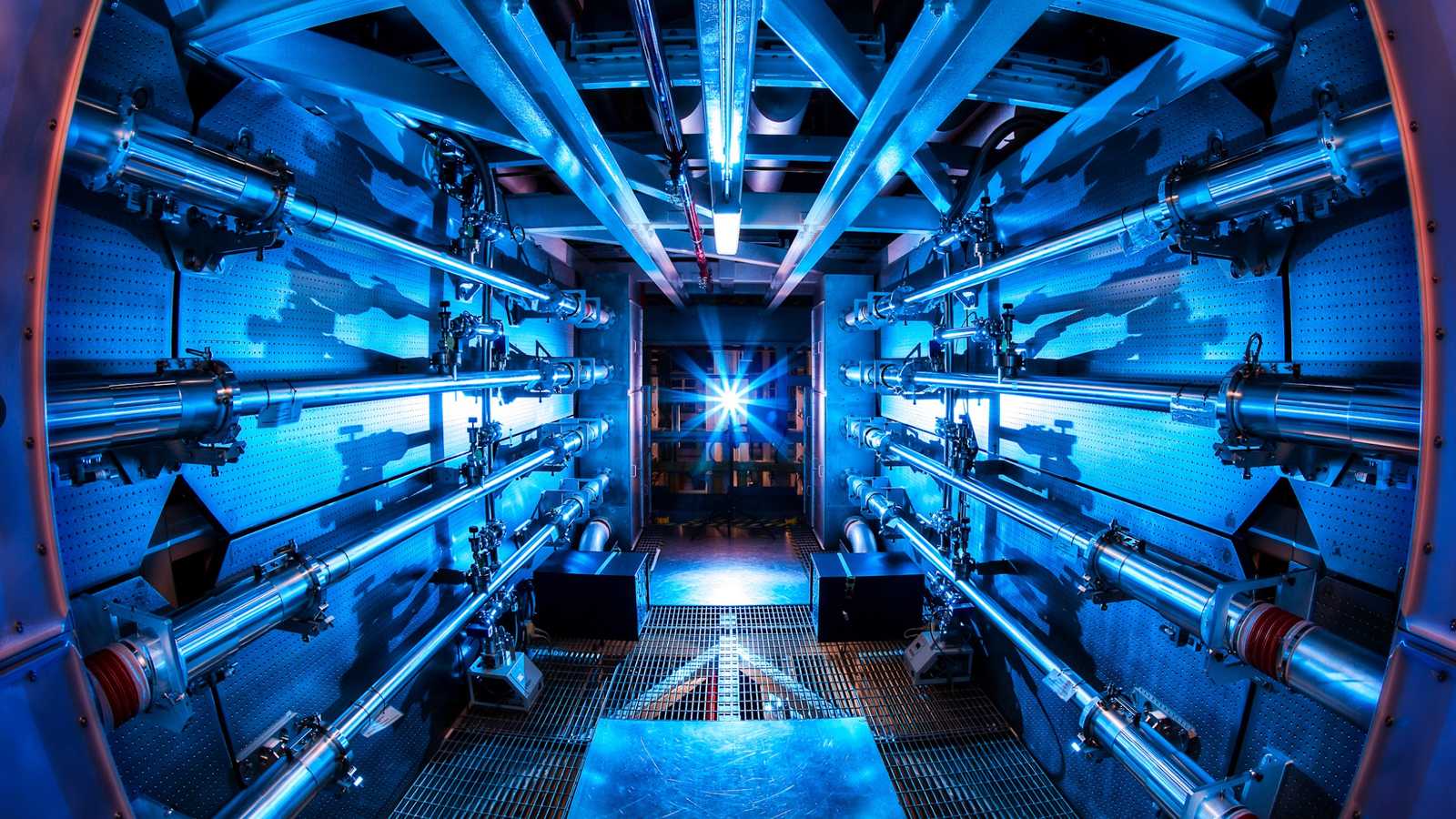

The experiment involved 192 high-powered laser beams being fired at a capsule containing the elements deuterium and tritium, heating it to a temperature of more than three million degrees centigrade – thus briefly simulating the conditions of a star.

Advertisement

Dr Marvin Adams said it had been carried out “hundreds of times before”, but had never successfully produced more energy than was consumed.

“For the first time, they designed this experiment so that the fusion fuel stayed hot enough, dense enough, and round enough for long enough that it ignited, and it produced more energy than the lasers had deposited,” he said.

“About two mega joules in, about three mega joules out – a gain of 1.5, the energy production took less time than it takes light to travel one inch.”

It was, as he quipped, “kind of fast”.

While the target was smaller than a pea, the lasers – part of the so-called NIF system – are powerful enough to deliver more energy than the whole power grid sustaining all of the US.

Chief engineer Jean-Michel Di Nicola said it was “the size of three football fields and delivers energy in excess of two million joules with a peak power of 500 trillion watts”.

“For a very short amount of time, a few billionths of a second, it exceeds the entire US power grid,” he said.

How long before the process can create useable energy?

The question on everyone’s lips following the news briefing was how long it would take before the process can be utilised for creating energy that we can actually use.

Dr Kim Budil, director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, admitted it would take “probably decades”.

President Joe Biden has said he hopes a commercial fusion reactor will be in place within 10 years, and officials acknowledged that the private sector would have to play a big role in accelerating the shift from lab experiments to commercial electricity production.

Other nuclear fusion projects will also have a role to play – and the scientists in California cited the work of a team in Oxfordshire, who earlier this year used their JET machine to generate around 11 megawatts of energy.

That was far more than was generated in the NIF experiment, but – crucially – did not achieve net energy gain.

Science and technology editor

As Dr Marv Adams was holding up the cylindrical target containing the “peppercorn-sized” pellet of fusion fuel, he confirmed they had achieved “ignition” of a fusion reaction.

He also revealed the scientists put about 2MJ of energy into their fusion reaction and got about 3MJ out.

That’s the evidence of the “energy gain” that this announcement is all about.

That’s the significant scientific milestone: proving a fusion reaction itself can generate more energy than you put into in.

But they had to use 300MJ of electricity to power up their lasers.

So from an energy production point of view, they’re still having to put in 99% more power into the machine as a whole as they are getting out.

University of Oxford Professor Gianluca Gregori, a specialist in the kind of lasers used at the lab, stressed that the amount of energy produced was smaller than that needed to power a wall plug.

“While this is not yet an economically viable power plant, the path for the future is much clearer,” he added.

Jeremy Chittenden, professor of plasma physics at Imperial College London, said scientists “will need to find a way to reproduce the same effect much more frequently and much more cheaply”.

If they do, it would be a huge shot in the arm for the world’s push towards renewables.