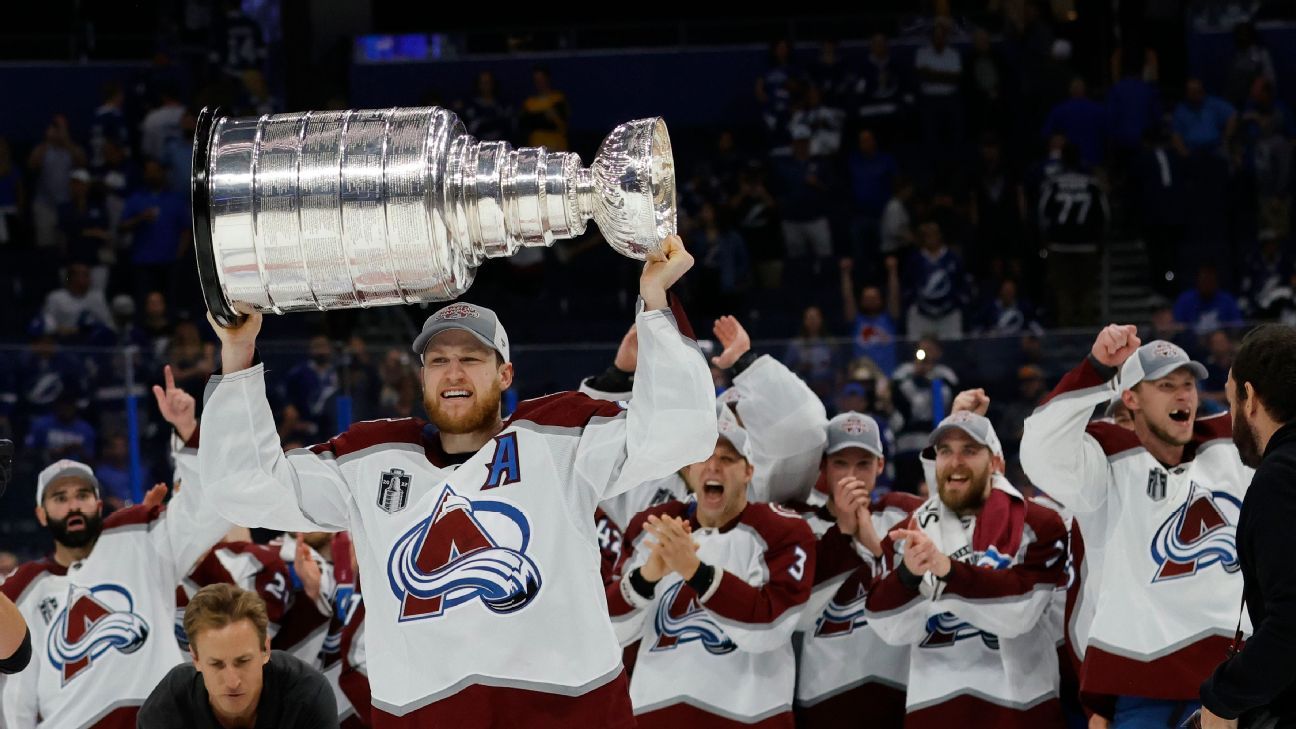

From ‘young and stupid’ to a leader of the Cup champs: Nathan MacKinnon opens up about his journey

DENVER — So, now that

This season will include 103 exclusive regular-season games across ESPN, ESPN+, Hulu and ABC. More than 1,000 out-of-market games will be available to ESPN+ subscribers via NHL Power Play on ESPN+.

• How to watch

• Subscribe to ESPN+

• Stream the NHL on ESPN

“It feels like I have had three different careers at once,” the 27-year-old MacKinnon said. “For me, it feels like my first three or four years was one career. Young, stupid, not a good player. My second three, four years, I established myself as a good player in the league. The last two, three years have been about maturity, trying to win Cups and focus on trying to become a good player.”

What makes him say the 18- to 22-year-old Nathan MacKinnon was “young and stupid?”

Anyone who has been around MacKinnon for even a minute knows he is direct, and that’s certainly the case in his assessment of his younger self. He points to his off-ice habits and the lack of maturity he showed at the rink. MacKinnon recognizes that he was just a teenager and smiles when he says it was as if he was in college.

“Then I hit a crossroads after we came [in] last. Do I want to be a good player? Do I want to be an average player?”

THE 2016-17 SEASON is still fresh for any Avalanche player or front office personnel who lived through it. The Avs finished with 48 points. At the time, it was the lowest point total in the salary cap era. Colorado’s season has to be considered among the worst in NHL history. MacKinnon was 21. He scored 16 goals and had 53 points in 82 games. It was not bad, but it was short of the 24 goals and 63 points he accumulated as a rookie when he won the Calder Trophy in 2013-14.

“You try to lie to yourself about how things are going, but being mediocre just doesn’t sit well with me naturally,” MacKinnon said. “It wasn’t like a huge change. Because my whole life I sacrificed everything to be a great player as a kid. I ate well, I worked so hard. Then I got to the NHL and lost my way a little bit. It wasn’t like an ‘I found Jesus’ moment. But I got back on the rails. I knew how to do this stuff. I had done it my whole life. I just had to find it again.”

The MacKinnon who emerged from the depths of the 2016-17 season is the one everyone had been waiting to see for some time. He broke through to score 39 goals with 97 points in 74 games, helping the Avs reach the playoffs for the first time in three seasons. As a result, MacKinnon was in the Hart Trophy discussion for the NHL’s most valuable player.

He finished second to Taylor Hall in Hart voting that season. (Two years later, MacKinnon was second in the Hart balloting again, behind Leon Draisaitl.) MacKinnon said the runner-up finish to Hall angered him, but it eventually became another inflection point in his life and career.

After losing out to Hall, MacKinnon said it took him two months before he realized he could not let the decision made by voters affect how he felt. He came to accept the reasons why he lost, acknowledging there were players better than him.

“The guys who beat me out deserved it. Hallsy and Draisaitl had unbelievable years. They’re unbelievable players,” MacKinnon said. “You’re still upset. You still want to win it. But at the end of the day, you can’t put all your happiness into how people vote and that’s OK. What matters is the guys in the room, your family and friends. After that, you can’t control what others think.”

Statements like that illustrate why Erik Johnson says the mental part of MacKinnon’s game has caught up to his physical exploits. Johnson, 34, is the Avalanche’s longest-tenured player and has watched MacKinnon’s evolution firsthand. He knows how difficult the adjustment can be for a young player entering the league, as he was a No. 1 pick who played in the NHL as a teenager himself.

“Sometimes, it’s hard to put the mental wear and tear and grind of a season together right away,” Johnson said. “He really developed to where he is doing everything possible to be the best he can be.”

FOR MACKINNON, THAT included becoming a better leader. Losing the Hart provided a silver lining in that it was further proof he was among the best in the game. The next step was finding a way to take what he learned to become a better player and use it to make the Avalanche a better team.

That meant sitting down with Andre Burakovsky, now with the Seattle Kraken, and encouraging him to shoot more after looking at his advanced metrics. And working with Matt Calvert, a bottom-six forward who was on pace for his first 20-goal season before injuries and the pandemic-shortened season in 2019-20 derailed those plans. Even so, Calvert still made significant changes, such as working with a skating coach to revamp his skating. Another was altering his diet. He credited MacKinnon for that change, and MacKinnon said it all came from Calvert and nothing more.

Thanks to Nikita Zadorov, the world gained more insight into MacKinnon’s nutrition plan. Zadorov, now with the Calgary Flames, said in a 2021 interview that MacKinnon had desserts, ice cream and soft drinks removed from the team’s dressing room and even played a part in having the team stop serving carbonara sauce with pasta, replacing it with a healthier option.

As Zadorov said, with those moves, MacKinnon “made pros” of the entire team.

“It’s not just about his success, not that it was before either,” Avalanche coach Jared Bednar said. “Now he thinks more about, ‘What does the team have to do?’, ‘How does it all fit together?’ He’s a bigger picture guy. A guy like [Gabriel Landeskog] has had that perspective for a number of years where Nate’s grown into that the last six years. It’s been getting better year after year, and last year, he was an incredible leader for us.”

MacKinnon knew he’d have to ease into that role. He said having Landeskog around as the Avs’ captain helped because it gave MacKinnon the time to both find his game and find his way into becoming a leader who could make a difference.

One of the steps MacKinnon has taken is to ensure young players feel valued. Perhaps the starting point for that was his relationship with Cale Makar. Earlier in Makar’s still young career, MacKinnon spoke about the Calder Trophy winner as if he raised him as his own while raving about how Makar was already one of the best defensemen in the league.

He pointed to Bowen Byram, saying the 21-year-old was their third-best defenseman in the playoffs last year and rattling off his stats. He continued by saying players like Byram, who are still on their entry-level contracts, are so important because their performances are what help Stanley Cup contenders with high-end players and big contracts have depth.

“It’s a lot different now than when I came into the league,” said MacKinnon, who made his debut in 2013, when Byram was 12. “So I like to relate to them. It’s tough being a young guy. Nowadays, you need young guys to win. It’s not like the old days when you treat rookies like s—. You need them.”

MacKinnon said he loves talking to his teammates about, well, anything. So how does that work when it comes to having a difficult conversation if someone’s not playing well? MacKinnon said the time he has spent with teammates has given him a gauge for what works. He knows some players may respond well to one approach while others may not. For him, it is about crafting a message and delivering it in a way that is more about togetherness than admonishment.

Avs star right winger Mikko Rantanen said MacKinnon has become more patient than he was five years ago.

“I saw it especially in the playoffs,” Rantanen said. “He was really calm in situations. If we had a bad period, he was just calm and just encouraged everyone to reset. There was a difference and it was fun to watch.”

What made MacKinnon want to become a better leader, let alone a leader at all? He could have just settled for being the best player on a team and nothing more.

“It just doesn’t feel good when you try to be the best player you can be and I knew that we weren’t going to win if I did not become even better of a leader and try to make guys feel good and make guys excited or try to be the best they can be,” MacKinnon said. “We were so close and figured if I gave it a shot last playoff run, especially try to make guys feel good every day — and that’s not saying it’s why we won — but every little thing guys do adds up.”

The notion MacKinnon is willing to open up about what got him to this stage of his career might be the strongest sign of his evolution. There was a time when MacKinnon would get angry enough with himself at practice, he would launch his stick into the stands at Ball Arena. It would sail 10 or so rows up, requiring an equipment manager to retrieve it while MacKinnon got another one.

Rantanen smiled when saying MacKinnon had managed to cut down on those moments, but admitted they do still happen from time to time. And while MacKinnon tossing his stick in the stands was too striking to ignore, it was something people did not really ask him about.

But now? He’ll talk about it freely.

“I don’t mind that. I like when guys get angry,” MacKinnon said. “We were at an optional skate and [Kurtis MacDermid] punched a water bottle the other day. I like it. I don’t think it’s a bad thing if I do that. I threw my stick the other day. It doesn’t matter.

“I just think away from the rink, you have to prepare yourself to be a leader, a good person coming into the rink and then have that energy before you show up. My whole thing is the work should be done before you play.”

A lot has changed in the six years since the low point of the Avalanche’s 48-point season. MacKinnon no longer has to ask himself if he wants to remain a mediocre player. His focus has shifted toward asking what can be done to get a few more banners hanging in the rafters of Ball Arena.

So does this mean MacKinnon is finally going to chill?

You probably can guess the answer. No, he is not.

“This is my journey and everyone’s different,” MacKinnon said. “Some guys come in and dominate. Sid [Sidney Crosby], [Connor] McDavid, [Auston] Matthews, those guys. I didn’t. I had to kind of find my way and I think once I found my way for three or four years, I focused more on trying to help others out and not just trying to make myself good. That’s how you win.”